( Revision March 27, 2022: I have moved Hynek's reply here. Vallee's reply is in the second part.)

Now that Jacques Vallee is back in the news (again) after being selected to join Dr. Avi Loeb's Galileo Project, it's instructive to review some of his earlier writings. Researcher Curt Collins points out that Vallee has been named to Galileo's "Research Team," which is higher than being a mere "Research Affiliate" like Galileo's other UFOlogists (Luis Elizondo, Nick Pope, Chris Mellon, Robert Powell, Gary Voorhis.). Did you see how many people are now listed on the Galileo web pages, in various positions? I didn't count them, but I was surprised to find dozens!

I had two book reviews published in the Spring/Summer, 1977 issue of The Zetetic (later to become The Skeptical Inquirer): this one by Hynek and Vallee, and Vallee's The Invisible College, which is in a later posting here.

Make no mistake, it was always Vallee pulling Hynek to be farther and farther out, rather than the other way around.

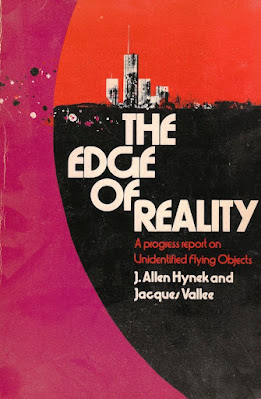

The Edge of Reality: A Progress Report on Unidentified Flying Objects.

By J. Allen Hynek and Jacques Vallee. Henry Regnery Co., Chicago, 1975.

301. pp. $14.9S cloth, $5.95 paper.

Reviewed by Robert Sheaffer (The Zetetic, Spring/Summer, 1977)

|

| Hynek at Northwestern about 1970 (photo by author). |

To categorize all UFO skeptics, including such experienced investigators as the late Donald Menzel and Philip Klass, as “people who have not bothered to learn the basic facts” is nothing short of an outrageous falsehood. Hynek should publicly apologize for having so recklessly published such foolish charges. Here we see the unstated principle upon which the “scientific” UFO Center operates: Responsible criticism does not exist. Questions and disagreements are invariably ignored. Letters from responsible (but unwelcome) individuals remain unanswered. Results of UFO evaluations are never publicly released. (Why give out such information to just anybody?) Thus the operation of the center has come to closely resemble the astrophysicists’ conception of a Black Hole; no matter how much material falls into it, nothing ever escapes. Yet the authors brazenly accuse all the other UFO groups of “actually hiding information instead of revealing it"! “They're publishing just enough to titillate the interest of their subscribers,” charges Hynek, whose group publishes virtually nothing at all, while imploring its subscribers to become patrons at a thousand bucks a throw. “They turn into a PR organization,” says Vallee of every UFO group except his own.

No meeting or conference organized by the Center for UFO Studies has ever included a single skeptic's dissenting voice. (Is the pro-UFO position utterly indefensible?) The house of cards Vallee and Hynek have built upon a foundation of hearsay evidence, careless scholarship, and neglect of scientific methodology would quickly tumble down in the turbulent air of open scientific debate. Having taken such pains to isolate themselves from all responsible criticism, it is not difficult to see why the authors now totter so precariously on the “edge of reality.”

Sheaffer's concern seems to be that the book is not a definitive work on UFOs. He fails to recognize the primary nature of the book: a conversation between two people who have devoted far, far more time than the reviewer to the subject, and who are themselves by no means in agreement on many aspects of the problem. The Edge of Reality was meant to be controversial, and even deliberately “visionary"; to exhibit the many sides of the problem of dealing with the phenomenon of UFO reports, whose existence no one can deny; and indeed, to parade to public view the authors' own puzzlement about UFOS. It was not intended as "UFO truth once and for all revealed."

Sheaffer has always totally ignored the continuing flow of truly puzz1ing UFO reports, from all parts of the world and in many instances from remarkably competent witnesses. He still undoubtedly be surprised by the results of Dr. Sturrock's recent survey of the membership of the American Astronomical Society on the subject of UFOS (Peter Sturrock, Stanford University Institute for Plasma Research Report No. 681), which points out that 53 percent of the respondents to the questionnaire (52 percent of the questionnaires were returned) indicated a positive attitude toward the scientific study of UFO reports, and which also contains a few interesting UFO reports made by professional astronomers!

The reader will discover that Sheaffer has learned well at the feet of his master, Philip Klass, the not-too-gentle art of using argumenti ad homini: “Their aim is to become Galileo, Einstein, and Daniel Boone all rolled into one” is a most uncalled-for remark. Further, his charge that we “have gleefully swallowed a dismally high number of UFO hoaxes” is certainly not demonstrable. Hoaxes by whose standards? Is Sheaffer unaware of Dr. Bruce Maccabee's work on the McMinnville photographs (see the Proceedings of the 1976 CUFOS Conference, Center for UFO Studies), which showed from careful photometric study that the strange object had to be at a considerable distance from the camera? Also, what about the utter lack of substantiation of Klass's claim that Socorro was a hoax contrived by the Chamber of Commerce to attract tourists? A recent visit to Socorro failed to reveal any improved roads (our rented car could not navigate the road to the site, and when a four-wheel pickup was used, the primary witness, Zamora, spent 15 minutes trying to locate the site). There were no signs or markers in the town, nor have there ever been any, to indicate that here is where the UFO landed. No concession stands capitalize on the “tourists.” If this is the sort of proof of hoax that Sheaffer accepts... ! With respect to the Pascagoula incident, I feel that Hickson was justified in refusing to take a polygraph test in the midst of a public conference, with all the “circus atmosphere” such a forum implies. In light of such errors of fact, I must have more than this reviewer's opinion that some of the cases Vallee and I have considered seriously are hoaxes and that we have “gleefully swallowed them.”

In stating that UFO skeptics are people who have not bothered to learn the basic facts, I was speaking of skeptics in general, with whom I have had ample contact in my many years of work in the area. I have found very few skeptics who are informed on the subject of UFOs. There will always be a handful who have diligently studied any subject but choose to interpret the facts to fit their emotional biases. Think of those who still feel that the Apollo mission was staged on a movie lot in Arizona! Or the people who know that one can circumnavigate the globe, yet force-fit this fact into their flat-earth theories!

It is psychologically expensive, and wasteful of time and energy, to join in battle with such skeptics. Should NASA have delayed mounting the effort to go to the moon until they had convinced the Astronomer Royal (who stated in 1955, “Space travel—utter bilge!”) that it was feasible? They had more important things to do. The success of the missions automatically disposed of the Astronomer Royal and his myopic ilk without one word of needless argument from NASA!

Sheaffer would have the Center for UFO Studies use its limited staff to tilt with the skeptics. We have chosen instead to publish, in our short history, many hundreds of pages of case reports and technical papers (e.g., The Lumberton Report; Physical Traces Associated with UFO Sightings; A Catalogue of 200 Type-1 UFO Events in Spain and Portugal, and 1973—Year of the Humanoids). The Center contributes to a new publication, The International UFO Reporter, which involves the careful investigation of every report included in each issue, and the Center also maintains a computerized file (UFOCAT) that now contains over 80,000 entries. Thus we dispose of Sheaffer's “black hole" theory; he chooses to remain “gleefully” unaware of the products of the Center.

All in all, Sheaffer's unfounded criticism, while revealing his emotional bias and its effect on his judgment, is hardly germane to the contents of the book or appropriate to a scholarly review.

Am I “unaware” of Dr. Maccabee's recent work? Even Dr. Maccabee does not make the claim that his research proves that the object “had to be at considerable distance from the camera,” as Hynek would surely have known had he actually read the paper he cited.

“He fails to recognize the primary nature of the book ... [it] was meant to be controversial.” Is there not some better way to be controversial than to rush into print with reckless errors or fact, such as in the table of “Astronaut Sightings" (Chapter 3) or the badly misrepresented Walesville “UFO" incident (Chapter 5)? This sloppiness is not a necessary consequence of informality. Am I just nitpicking? Or should this gross carelessness serve to alert us that much, if not all, of the authors' UFO theorizing may be built on a house of cards?

With regard to the Pascagoula incident, Hynek apparently conceded defeat concerning the first polygraph fiasco, but defends Hickson's refusal to face the machine a second time. He fails to mention, however, that Hickson had agreed to the polygraph test as a condition for being invited to the conference, but then backed out after his arrival. Is this action “justified"? Concerning Socorro, I find myself being lambasted for the alleged shortcomings of someone else's analysis of the case, a case not mentioned by me anywhere in my review either directly or indirectly. (I agree that Klass's evidence for a Socorro hoax is not overpowering. But is his explanation as far-fetched as the alternative?)

In light of the above, which of the two of us is guilty of the “errors of fact” that Hynek alleges?

Especially revealing is Dr. Hynek's automatic reduction of all skeptics to the level of flat-earthers and the faked-Apollo-flight nuts. (Who accuses whom of argumenti ad homini?) Disagree with me, says he, and you shall be dropped into the dustbin of History. If the voices of Galileo, Einstein, and Daniel Boone were to all be rolled up into one, would they not speak thusly? (One detects an accent of Zarathustra's voice as well.) Is Hynek “unaware” that both NICAP and APRO have told their members that Klass's investigations represent a significant contribution to UFOlogy and that his book UFOs Explained should be studied by everyone interested in UFOs, even though these groups strongly disagree with Klass's ultimate conclusions? The Center for UFO Studies makes no such concessions to the ravings of flat-earthers, UFO skeptics, and other crackpots. They have no time to “tilt” with unbelievers, as if with so many windmills. (Who is it that suffers from an “emotional bias”?) Dr. Hynek has convincingly illustrated my point that the “scientific" UFO Center operates on the principle that “responsible criticism does not exist.”

Lest the reader conclude that the matter reduces to irreconcilable mutual charges of “emotional bias,” consider this point: in a recent article (Official UFO, October 1976), I have plainly stated the type of evidence that would, if obtained, cause me to reconsider my position as a UFO skeptic. (They needn't land at the White House.) Let Hynek now point to the place where he has described the evidence that would cause him to change his opinions.

My chances of being laughed at along with the flat-earthers in the judgment of history are considerably smaller than the risk Dr. Hynek now runs of being accorded a place alongside the supremely credulous Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

| |

| Hynek was correct that in 1977 there was no marker to designate Zamora's sighting - but there is today! (Photo by Ryan Gordon.) | |